Fernand Thibaut

fig. 1

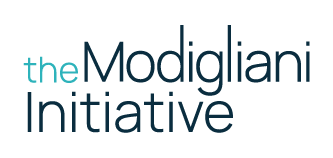

Amedeo Modigliani, A Man, 1916, oil on canvas.

Detroit Institute of Arts, Bequest of Robert H. Tannahill, 70.186.

October 28, 2023

Reclaiming a Model’s Identity:

A Case Study in Provenance Research

Provenance research can lead to serendipitous discoveries. This is particularly true when researching the owners of Modigliani’s portraits because of the interconnectedness of the artistic community living and working in close proximity in Paris in the years leading up to and during the First World War. Many of Modigliani’s friends and associates were not only his models but some were among his earliest collectors.

Because of the scarcity of archival records pertaining to Modigliani and his artwork, the identification of his models enriches our knowledge of the artist. A number of these individuals are known through Modigliani’s own inscriptions that appear on the face of a painting or noted on a drawing. But for those whose identities have been lost, a chance discovery can result in a fascinating connection.

Oscar Miestchaninoff (1886–1956) is the subject of two Modigliani paintings, dated 1916 and 1917, and a handful of drawings. (fig. 2) Born in Vitebsk, he had arrived in Paris a decade earlier and may have met Modigliani through Chaïm Soutine (1893–1943), who came from Lithuania and was Modigliani’s good friend.

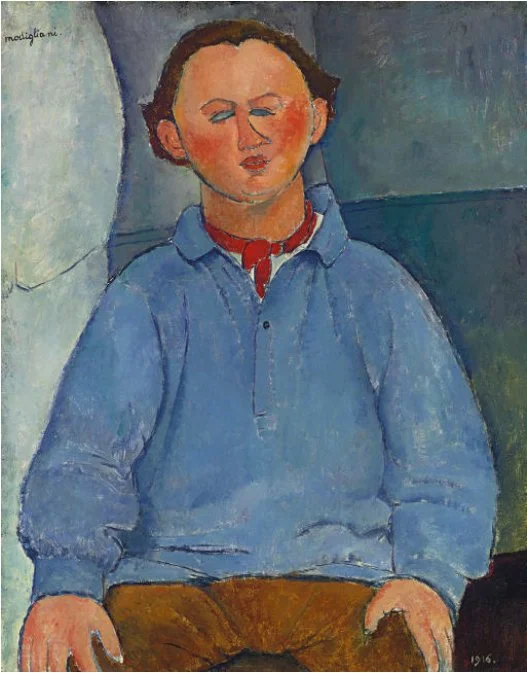

fig. 2

Oscar Miestchaninoff, 1916.

Present whereabouts unknown

Miestchaninoff’s success as a sculptor allowed him to assemble a significant art collection which he displayed in his studio-residence designed by Le Corbusier in 1925.[1] At one time, his collection included the Modigliani portrait, A Man, which he sold in December 1920 to Galerie Bernheim-Jeune.[2] (fig. 1) The prestigious Parisian gallery began actively buying Modigliani’s paintings several months earlier, not long after the artist’s untimely death in January.[3]

In 1941, Miestchaninoff and his wife Beatrice left Paris and relocated to New York. They brought with them an assortment of works from their collection and are known to have sold a handful of these over the years.[4] Not long after her husband’s death in 1956, Beatrice presented Miestchaninoff’s Portrait of Ferdinand F. Tibeau, the Painter, 1919, to the Cleveland Museum of Art. (fig. 3) Other than this descriptive title, she did not provide the museum with any further details about the sitter’s identity.[5]

fig. 3

Oscar Miestchaninoff (French, 1886–1956), Portrait of Ferdinand F. Tibeau, the Painter, 1919. Bronze; overall: 43.2 cm (17 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Beatrice Miestchaninoff 1957.393.

Courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art

The fact that Miestchaninoff kept the 17-inch-tall bronze bust for his entire life is intriguing, especially when combined with the fact that the sculpture bears an uncanny resemblance to the Modigliani painting he had owned decades earlier. The two portraits share distinct features: the man’s receding hairline and the angularity of his right cheek (possibly a scar?) and begs the question: who was “Tibeau, the Painter?” (figs. 4, 5)

fig. 4 (left)

Modigliani, A Man, 1916, oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of Arts, Bequest of Robert H. Tannahill, 70.186.

fig. 5 (right)

View 2: Miestchaninoff, Portrait of Ferdinand F. Tibeau, the Painter, 1919. Cleveland Museum of Art.

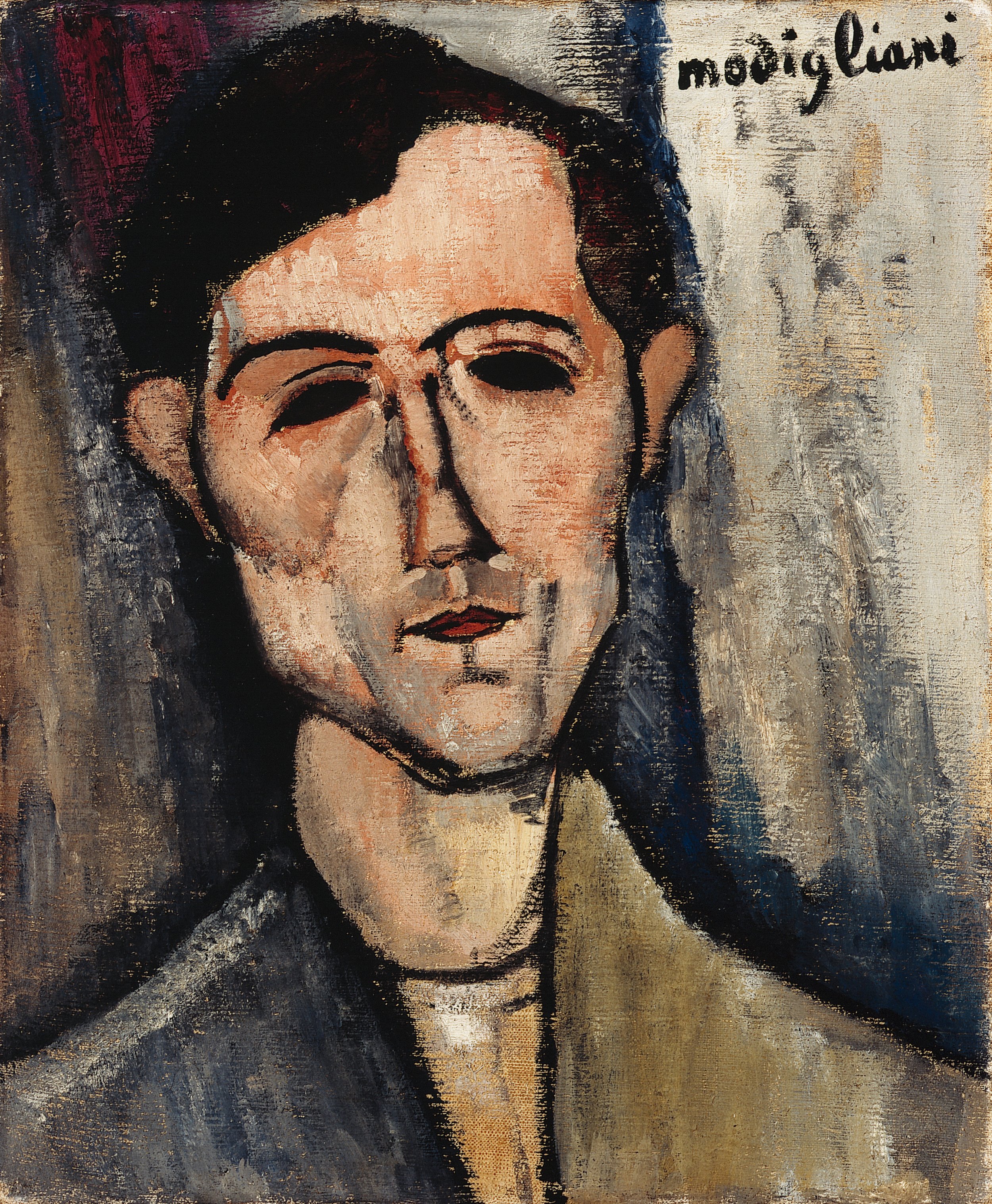

Miestchaninoff’s sculpture was shown and reproduced in publications a handful of times, first in Europe, beginning in 1925, and later in the US. The spelling of the model’s name varied over the years, ranging from “F. Thibault” to “F. Tubeaut” to “Painter Thébaut.”[6] Interestingly, Modigliani’s inscription on a Cariatide work on paper, from 1911–12, offers a tantalizing clue.[7] (figs. 6, 7) Next to his signature, Modigliani added the note: “à Tibaut bien amicalement,” indicating that the watercolor was likely a gift from the artist to his good friend. It turns out that 14 Cité Falguière, the artists’ studios where Modigliani lived between 1909 and 1912, was also the home of Fernand Thibaut (1879–?), who lived at this address by 1912 until at least 1938.[8] Miestchaninoff moved into the neighboring studio at 7 Cité Falguière in 1913.[9] Other than the fact that Miestchaninoff and Thibaut were neighbors for several years and the former immortalized the latter in bronze, no accounts chronicling their relationship have been located to date.

fig. 6 (left)

Modigliani, Cariatide, 1911–12.

Present whereabouts unknown

fig. 7 (right)

Cariatide, 1911–12, detail of Modigliani’s inscription: “à Tibaut bien amicalement”

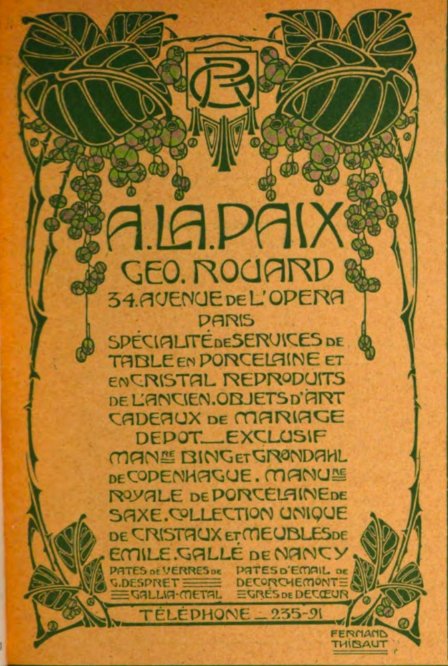

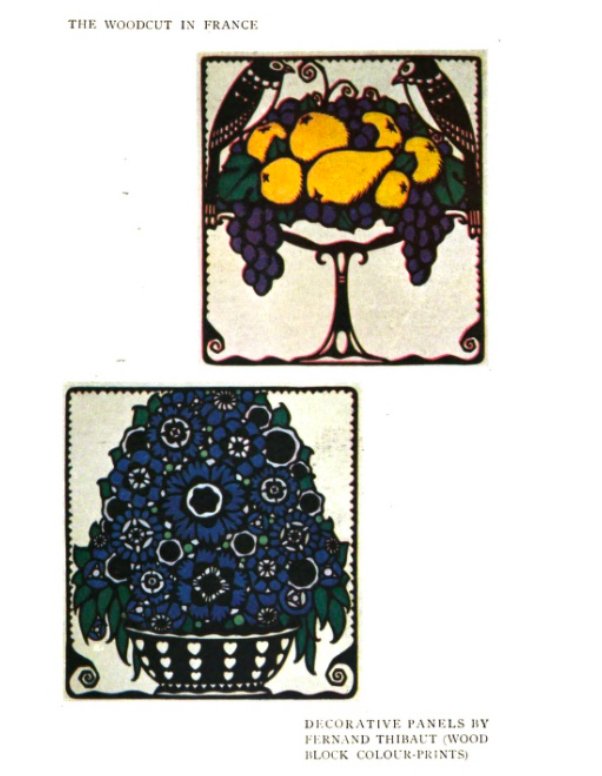

Records for Fernand Thibaut are scarce. (fig. 8) Born in Leuven, Belgium, he was living in Paris by 1903 when his work was included in the decorative arts section of the first annual Salon d’Automne.[10] A range of his artwork—stained glass, carpets, and woodblock prints—appeared with some regularity in subsequent Salons until 1938, as well as in other exhibitions in Paris during this time.[11] Between 1908 and 1909, Thibaut created sumptuous ads in the Art Nouveau style for the luxury goods store A La Paix. (fig. 9) Examples of his woodcuts were selected for inclusion in a book published in London in 1919. (fig. 10)

fig. 8

1907 advertisement for Fernand Thibaut’s decorative services

Supplément, L’Art decoratif 18 (August 1907): n.p.

fig. 9 (left)

Fernand Thibaut, Advertisement for A La Paix, 1908.

L’Art decoratif 18 (January 1908): n.p.

fig. 10 (right)

Fernand Thibaut, woodblock prints published in color in Modern Woodcuts and Lithographs by British and French Artists, Geoffrey Holme, ed. (London, Paris, New York: The Studio Ltd., 1919), 79.

Thibaut’s exhibition records can be fleshed out with a few personal details. The Portuguese painter Diogo de Macedo (1889–1959), who lived at 14 Cité Falguière between 1911 and 1913, wrote a book about the famed studios and his colorful fellow occupants.[12] He recalls that “the Belgian Thibeauth” was a talented artist who worked in a range of mediums, describing him as a “tasteful decorator, stained glass artist, mosaicist, ceramicist, painter.”[13] Macedo cryptically notes that Thibaut was having an affair with a wealthy older woman.[14]

In fact, Fernand Thibaut was romantically linked to the British painter Lilian de Glehn (1872–1951), sister of the well-known Impressionist painter Wilfrid de Glehn (1870–1951).[15] By 1911, Madame de Glehn’s marriage to Edouard Rist, a highly respected professor of medicine in Paris, had ended. According to family lore, her “running away” with Thibaut from her husband and the couple’s young son scandalized the extended family.[16] Lilian and Fernand lived together at 14 Cité Falguière for over two decades.[17] Her work was regularly included in the Salon des Tuileries and the couple collaborated with Haviland, the maker of fine china, providing designs for china patterns until at least 1928.[18]

The trail for Fernand Thibaut goes cold after the 1938 Salon d’automne. Despite slim documentation on his life, he was more than a painter with an easily misspelled name. When pieced together, the portraits created by his friends, along with the published records of his artwork, help reconstruct the story of his forgotten life and attest to the hereto unexamined friendship between these artists.

Julia May Boddewyn

The Modigliani Initiative would like to thank the Detroit Institute of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art for providing us with the images of the works published in this essay. Special thanks to Alessandro De Stefani, whose generosity in providing his expertise, not only on 14 Cité Falguière but also on Modigliani’s drawings, helped make this essay possible. Sophie Raobeharilala also kindly shared her findings on Thibaut, enriching this essay.

Endnotes

Anna Jozefacka, "Oscar Miestchaninoff," The Modern Art Index Project (March 2017), Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Link)

Guy-Patrice and Floriane Dauberville, Modigliani: Amedeo Modigliani Chez Bernheim-Jeune (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 2015), no. 57, as Portrait d’homme, p. 150. For more information on the painting, see the Detroit Institute of Arts’ website.

The gallery first began buying Modigliani’s work in early September 1920 and, within three months, acquired twelve paintings by the artist. Ibid.

Suggesting his fond memories for his friends in Paris, Miestchaninoff brought with him to the US, not only his sculpture of Fernand Thibaut, but also at least three paintings by Soutine: Portrait du sculpteur Oscar Miestchaninoff, 1923–24 (Centre Pompidou, Paris. Gift of Mme Miestchaninoff, 1972); L’Atelier de l’artiste à la cité Falguière, 1915–16 (sold at Sotheby’s, New York, November 19, 2020, lot 46); and Still Life with Rayfish, c. 1924 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). He also brought his watercolor Portrait of Diego Rivera, 1913 (Cleveland Museum of Art) and at least two drawings of himself by Modigliani that he sold through Knoedler in New York. One is in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Gift of Peter Pflaum and Stephen R. Pflaum (2015.130.2) and the other, current location unknown, was exhibited by Knoedler in the 1961 Modigliani exhibition held in Boston and Los Angeles.

I am grateful to Beth Owens, Research and Scholarly Programming Librarian, Ingalls Library, Cleveland Museum of Art, for checking the records of this sculpture for additional information. Email of September 15, 2023. Further details about the sculpture on the museum’s website can be found here.

Yvanhoe Rambosson, “Oscar Miestchaninoff,” Art et Décoration XLVII (February 1925): 64; “Sculpture and Drawings by Miestchaninoff,” exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1944), no. 5, n.p.; Waldemar George, Oscar Miestchaninoff. Sculptor, Explorer, Collector. (Paris: Arts et Métiers Graphiques, 1966), 24, ill. in b/w.

This watercolor was sold at Bonham’s in London on June 27, 2007, lot 30.

Thibaut’s Cité Falguière address is first listed in the 1912 Salon d’automne exhibition catalogue. Salon d’automne 1912: 10e exposition (Paris, 1912), 31. This address appears regularly for him until 1938. Catalogue des ouvrages (Paris: Société du Salon d’automne, 1938), 56. In this catalogue, Mme. Liliane de Glehn-Thibaut is listed on p. 34. For more on 14 Cité Falguière and its residents who overlapped with Modigliani, see Alessandro de Stefani, “Modigliani alla Cité Falguière: la prima fase della scultura nel suo contesto immediato,” Studiolo 12 (2015): 242–67. Thibaut’s name is not included in De Stefani’s list of painter/sculptor residents because he was technically considered a decorative artist by the Salons.

Miestchaninoff is listed at 7 Cité Falguière in a 1914 trade directory. Annuaire de Commerce Didot-Bottin (Paris, 1914), 477.

A.-E. Guyon-Verax, “Comptes rendus des expositions, Société nationale des beaux arts: Salon de 1903, Sculpture, Art décoratif, etc., etc.,” Journal des artistes 28, no. 28 (August 2, 1903): 4195.

In 1903, Thibaut won honorable mention for his monogram design “Nadia.” “Awards in ‘The Studio’ Prize Competitions,” The Studio International 20 (New York, 1903): 74. In addition to his inclusion in the Salon d’automne in 1909, 1912, 1913, and 1919 (and possibly others that could not be readily confirmed), his woodblock prints were reproduced on the pages of L’art décoratif and shown in Exposition de la jeune gravure sur bois, Galerie Devambez, Paris (December 17, 1919–January 30, 1920). Thibaut’s stained glass was displayed at the Musée Galliera, Paris in June 1923 in an exhibition of modern glassware and enameling. His name appeared with some frequency in the press during these shows.

Diogo de Macedo, 14 Cité Falguière (Lisbon 1930).

Ibid, 25.

Ibid.

On his website, Mark Hill published a wonderful essay titled, “A Forgotten Woman Artist: Lilian de Glehn Thibaut” about his discovery of a painting by de Glehn-Thibaut. The painting is inscribed on the reverse with her name and the couple’s 14 Cité Falguière address.

I am grateful to Mark Hill for generously sharing these details about de Glehn and Thibaut. Email dated September 28, 2023.

Catalogue des ouvrages (Paris: Société du Salon d’automne, 1938), 56.

Ernest Weber, “Les Arts du feu et le grand ‘dépot,’” L’Art et les artistes XVII, no. 85 (March 1, 1928): 317.